We’ve been talking about how a therapist can bill for compression in light of the passage of the Lymphedema Treatment Act. Last month, we noted there were (3) models. The third model involved:

- a therapist billing Medicare for compression as a supplier & for service as a provider for their own patients, and

- the same therapist also billing for compression for people who are not their patients.

This gets tricky because the model gives rise to unique ownership concerns related to Medicare & Medicaid payments. (Government complicates things.) These concerns revolve around federal statutes & criminal liability. That’s the focus of this month’s blog.

Disclaimer: Information is not guaranteed to be comprehensive or accurate. Consult a healthcare law attorney for guidance.

Model 3

You would think billing for other people’s patients could be done in your therapy business. But that’s not the case – unless the individual is your patient. And would another therapist want to refer their patients to you – a competitor? Of course, there are several people seeking compression that aren’t wanting treatment. They just need someone who can bill insurance. But does billing for a supply item constitute someone becoming a patient? Besides that, the 42 CFR has special considerations for therapists billing for compression for their own patients that doesn’t apply to therapists billing for individuals who are not their patients. (See April’s blog update.) A seemingly easy solution is to have a second business.

If you have a second business for DME, why not simplify things? Keep your therapy services in the therapy business & the DME in a DME business. You could have both businesses in the same location & save on costs (like rent). Additional benefits could include having a different taxonomy code (for potential better reimbursement rates), less confusion among insurance payors, & legal protection from financial losses. You could refer your therapy patients to the DME business. Right? Wrong. (Why not? Well, government complicates things.)

Medicare Supplier Standards2

Anyone who plans to bill federal healthcare programs for DME must be mindful of the 42 CFR Supplier Standards. One of those standards states a supplier is prohibited from sharing a practice location with another Medicare provider or supplier. But there are a few exceptions. Two of these include:

- a therapist (i.e. provider) who is billing DME for their own patients only

- a DME supplier can be co-located with & owned by a Medicare provider (e.g. therapist), but the businesses must operate separately (separate phone lines, separate computers, separate staff, etc.). You must also meet the definition of a Medicare provider.7,8

It would seem you actually could separate the therapy business & refer your patients to your DME company. But that’s not the case. (Did I mention government complicates things?)

The Anti-Kickback Statute

The Anti-Kickback Statute is one of the fraud & abuse laws mentioned last month. It was an amendment added to the Social Security Act & first passed by Congress in 1972 as an effort to prevent fraud & abuse of federal healthcare programs (i.e. Medicare & Medicaid).6 It can be found in Title 42 of the U.S. code which covers public health & welfare. (These laws are broken down into titles, chapters, subchapters, parts & sections.)3,4 Specifically, Section 1320a-7b talks about the Anti-Kickback Statute. This amendment prevents giving or receiving anything of value (e.g. money, free rent or other perks) for generating healthcare business paid for by federal programs.

In other words, if you had two businesses that billed Medicare or Medicaid, & you wanted to refer patients from one to the other, you can’t. (Unless, of course, you don’t mind jail time & hefty monetary penalties. Most therapists try to avoid these.) There are a few “safe harbor” exclusions that will allow such business transactions.5 But all elements of a safe harbor must be met. (And these have pros & cons.)

Two notes: First, this only applies to providers/suppliers billing federal healthcare programs (clarification is needed as to whether the non-direct plans like the exchange programs provided by commercial plans are included in this). Second, you can still have a therapy business providing therapy services & DME to your own patients. You can also have a separate DME business for other people’s patients in addition. But these must operate entirely separately & cannot refer business between them if you bill federal healthcare programs unless you fall within one of the safe harbor exclusions. You would also be wise to consider other mitigating factors to prevent implication of Anti-Kickback Statute violation.

There’s one more question that comes to mind regarding billing. What if a Medicare patient wants to pay cash for an item? We’ll look at that next month.

References

1 https://oig.hhs.gov/compliance/physician-education/fraud-abuse-laws/

2 (supplier standards) https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-42/chapter-IV/subchapter-B/part-424/subpart-D/section-424.57

3 https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2010-title42/USCODE-2010-title42-chap7-subchapXI-partA-sec1320a-7b

4 https://uscode.house.gov/

5 (safe harbors) https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-42/chapter-V/subchapter-B/part-1001/subpart-C/section-1001.952

6 https://www.whistleblowerllc.com/anti-kickback-statute/#:~:text=Congress%20first%20enacted%20the%20AKS,physicians%20corrupt%20medical%20decision%2Dmaking.

7 (clinic definition) https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2011-title42/html/USCODE-2011-title42-chap7-subchapXVIII-partE-sec1395x.htm, https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/downloads/R5BP.pdf & https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1861.htm

8 (OTPP definition) https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/downloads/R5BP.pdf

Attribution

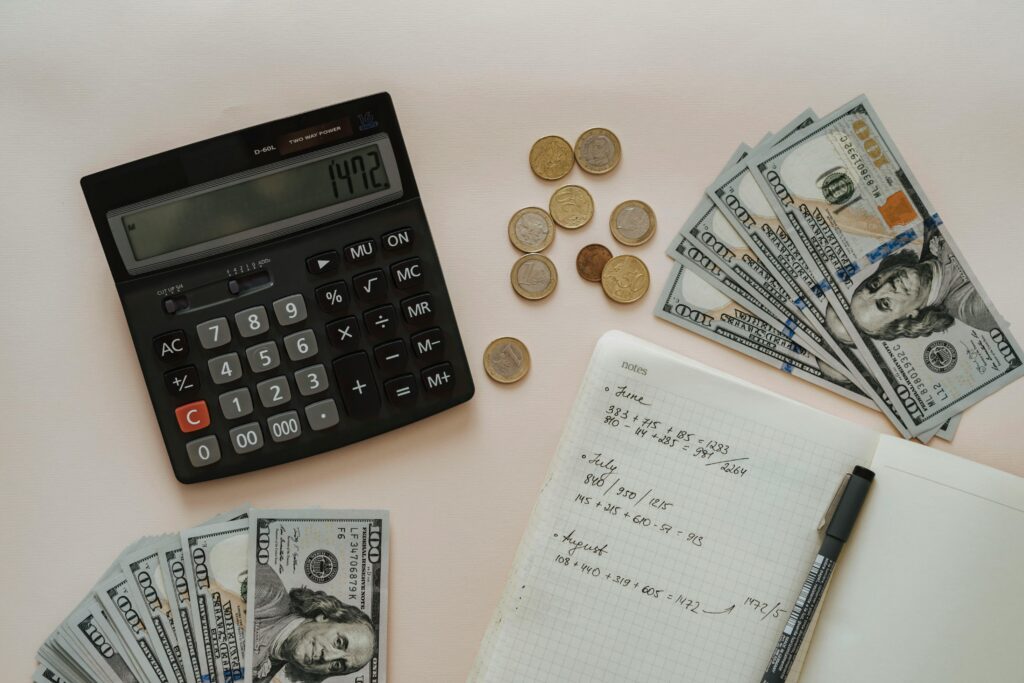

Photo by Olia Danilevich Pexels