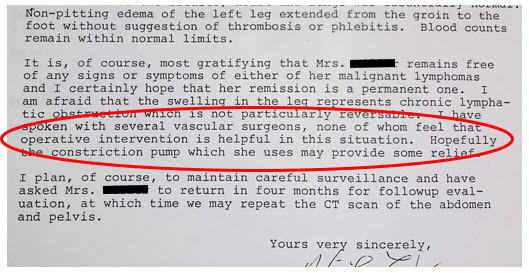

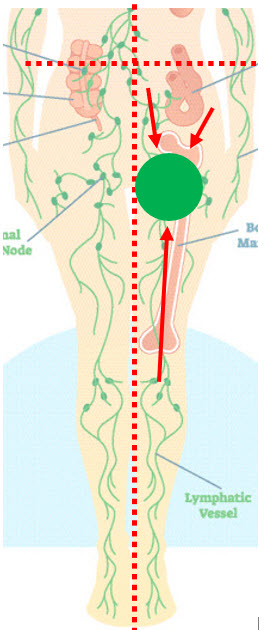

Jackie’s story of cancer & lymphedema coming in December. (Jackie was referred to as Janie’s earlier in the blog for anonymity. With the family’s permission, her real name is now being used.)

November will not have a post. Learning video editing is more arduous than expected! Stay tuned…